The lower part of our ranch, nestled in the valley along the creek—

below the mountains where our cattle go to summer range.

Today I’ll slip back in time again — and share with you some thoughts and memories inspired by notes in an old journal, written about 15 years ago. I’ll describe a typical day checking cattle on our range. I’ll take you along with me, in my remembrance and imagination.

Our cattle ranch lies at the foot of the mountains where our cows spend the summer. At that point in time, I was riding almost every day to check the cattle, make sure gates stayed shut, and see if all the water troughs were working. We live in very dry country, and our cattle depend on a few small streams for water and many water troughs. There are a number of springs and seeps that we’ve piped into troughs. Sometimes a spring box gets plugged with mud from a summer thundershower and needs to be cleaned out.

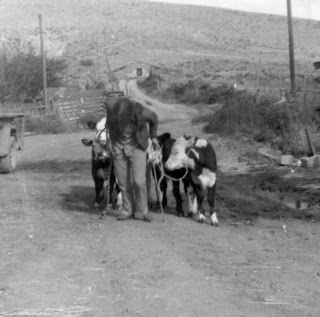

Our cattle spend the summer in the mountains behind our ranch;

here a group of cattle is herded toward the next range pasture.

Sometimes gates get left open and cows wander onto the wrong range — and must be located and herded back to their proper pastures. Sometimes a cow or calf gets sick and develops foot rot or pinkeye and needs to be brought home for medical treatment. If we ride out there often, we know what's going on and can attend to any problems.

Each ride is a unique experience. On a typical day I head up the steep trail through tall sagebrush across the road from our house. The smell of dewy sage fills my nostrils as my horse brushes the shrubs along the trail, and a horned lark flits up from her nest on the ground as we go by. A grouse bursts into the air and does her broken-wing act (as she would do to lead a predator away from her babies — who are hurriedly scattering through the grass).

Heading out from the ranch to ride range; in this photo our daughter Andrea

and daughter-in-law Carolyn are climbing up the hill above the ranch.

My mare breathes deeply as she climbs the crest of the hill, then pauses, snorting, as a group of antelope leap to their feet from the swale where they were bedded and bolt across our path. She snorts again as she inhales their strong, musky scent. They disappear over the hill in a puff of dust, and we continue along the trail.

We soon head down into Baker Creek canyon, approaching a brushy draw where a small trough collects spring water. A herd of cow elk and their calves have been drinking there, and they mill about for a moment when they see me — talking to one another with their high-pitched “eeep-eeep.” Then they stick their heads in the air and march up out of the draw, disgusted at having their morning interrupted.

We descend into Baker Creek and up the rocky trail into the timber, dodging overhanging fir branches. A golden eagle soars above the canyon, and a pine squirrel scolds from the tree overhead, knocking fir cones down into the trail. Colorful Indian paintbrush (red, orange, pale cream) and blue lupine dot the grassy clearing ahead. We reach the wire gate in the range crossfence, and I get off to open it and lead my mare through.

Some of our cattle lounging around in Baker Creek

In the meadow beyond, some of our cattle are bedded down, chewing their cuds. They are very accustomed to seeing my horse and don't bother to get up as I ride through them, weaving my way between napping calves. One calf is nursing his mother, slurping noisily at the udder. I make sure they are all healthy; then my horse and I continue up the trail to check another water trough.

The day is warm, and my horse takes a long, grateful drink while I fix the overflow pipe that’s been obstructed with fir needles. This spring comes directly out of the rocky canyon wall, and the water is icy cold — and more pure and clean than the boggy springs where elk like to wallow, so I quench my thirst from the in-pipe.

It's a steep climb to the next little creek drainage, but we wend our way in a roundabout fashion, stopping at each group of cows to check them. When we get over the mountain and head down the other side, there’s another trough in a grassy clearing, and here I let my horse graze for a moment as I eat a sandwich from my jacket pocket. My jacket, tied to the back of my saddle, holds not only my lunch but also a pocketful of baling twine for emergency fence repairs (I can always tie a broken wire back together or tie wires to a post if the elk have knocked the staples out) and small binoculars for checking cattle a long way away.

After this quick “lunch,” my horse and I travel through more timber, startling two mule deer bucks who leap gracefully over the fence and out of sight. We go around the mountain through an outcropping of shale rock, my horse carefully picking her way in the precarious footing. A family of rock chucks chirp and scold before disappearing into their holes.

One of the wire gates in the range crossfence. In this photo

my granddaughter is opening it and leading her young horse through it.

Cattle lounging on a bedground. One of the calves is

nursing his mother, slurping noisily at the udder.

I go another mile to check a gate in the fence between our range and the Forest Service allotment. A jeep track comes up that side of the mountain and into our range, and I check this gate often; sometimes folks neglect to shut it after driving through. While on the back side of the mountain, I find a group of yearling heifers — several miles from where I saw them yesterday. This is the “wandering” age group. They won't have calves till next year, so they are footloose and fancy free. Like a group of teenagers, they are always interested in seeing what's beyond the horizon, not wanting to miss out on anything exciting.

One of our troughs that collects piped spring water. In this photo our

grandson and granddaughter pause on a range ride to let their horses drink.

I am glad to find Boogie Woogie (daughter of Shimmy, sister of Tango; yes, all our cattle are named!) because I need to check her eye. She had early symptoms of pinkeye the last time I saw her, but today the eye looks better, so I won't have to bring her home for treatment. I'd rather not have to bring her home; bringing an unwilling critter home from the range can be a challenge even with a good horse. Yearlings are sassy and inexperienced in being herded. About the only way to get one of them home is to take a “babysitter” cow, too. The older cow is more likely to be somewhat cooperative (with more respect for the horse, not trying to outrun us and hide in the brush), and the yearling tends to stay with the cow. Yearlings are true “groupies”; they never like to be by themselves.

Calves enjoying the shade in a grassy clearing

I head back along the fence to check a gate in the timber and find a freshly knocked-down (broken off) post where a herd of elk went through. They usually jump the fences, but sometimes they’re lazy and knock them over. I'm glad I discovered this “hole” in the fence before the heifers did, or they'd be in the neighbors' range! Sometimes it can take days or weeks of riding to find cattle when they stray into the wrong range, so we like to make sure the fences stay in good shape. I prop the post back up and splice the broken top wire with my handy baling twine. This will hold the fence together until my husband can bring a new post up the ridge on his four-wheeler — and then carry it a quarter mile down the steep hill through the timber, to the fence.

Our daughter riding range, traveling around a slippery

mountainside through loose gravel and shale

It's hot by the time we start back to lower country, and my horse's feet stir up little clouds of dust. The sweet smell of syringa (the blooming bushes along the creek — Idaho's state flower) mixes delightfully with the smell of horse sweat as we cross the little stream; then my mare spooks as a coyote pup sticks his head up over an old log to look at us. Once my mare realizes what he is, she relaxes and continues on down the trail, quickening her pace as she thinks about home. Both of us are pleased with our ride. She's happy to be heading back to her pasture buddies, and I have enjoyed this peaceful interlude with nature — and pleased that we found no serious emergencies to deal with.

Riding one of my young horses, checking cattle, marking off

a heifer's number in my cow book. We mark off every

individual we see, each time we ride range.

Heather Smith Thomas raises horses and cattle on her family ranch in Salmon, Idaho. She writes for numerous horse magazines and is the author of several books on horses and cattle farming, including Storey’s Guide to Raising Horses, Storey's Guide to Training Horses, Stable Smarts, The Horse Conformation Handbook, Your Calf, Getting Started with Beef and Dairy Cattle, Storey's Guide to Raising Beef Cattle, Essential Guide to Calving, and The Cattle Health Handbook. You can read all her Notes from Sky Range Ranch posts here.